Biological warfare agents

Biological warfare is distinct from nuclear warfare, chemical warfare and radiological warfare, which together with biological warfare make up CBRN, the military acronym for Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear, warfare using weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). None of these are considered conventional weapons.Biological Warfare (BW), also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses and fungii with intent to kill or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. Biological weapons (often termed bio-weapons, biological agents or bio-agents) are living organisms or replicating entities (viruses are not universally considered "alive", neither are prions), that reproduce or replicate within their host victims, or toxins derived from living organisms. Entomological (insect) warfare is also considered a type of biological weapon, however insects are far more likely to be used as vectors of biological agents, than as weapons themselves, they might also be used to attack crops. There is an overlap between BW and chemical warfare, as the use of toxins produced by living organisms is considered under the provisions of both the Biological Weapons Convention and the Chemical Weapons Convention.

A country or a terrorist group that can pose a credible threat of mass casualties has the ability to alter the terms on which other nations or groups interact with it. Biological weapons allow for the potential to create a level of destruction and loss of life far in excess of nuclear, chemical or conventional weapons, relative to their mass and cost of development and storage. Therefore, biological agents may be useful as strategic deterrents in addition to their utility as offensive weapons on the battlefield. The effects of such a weapon are now more evident, perhaps than any time previously, because of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Whole nations had their manufacturing capacity reduced to virtually nothing for many weeks, international travel virtually came to a halt, and the financial impact is still unknown but, in the case of the USA alone estimates range from runs into 10 to 22 trillion US dollars.

As a tactical weapon for military use, a significant problem with a BW attack is that it would take days, weeks or even months to be effective, and therefore might not immediately stop an opposing force. Some biological agents have the capability of person-to-person transmission via aerosolised respiratory droplets. This feature can be undesirable, as the agent(s) may be transmitted by this mechanism to unintended populations, including neutral or even friendly forces. While containment of BW is less of a concern for certain criminal or terrorist organizations, it remains a significant concern for the military and civilian populations of virtually all nations.

It has been suggested that rational state actors would never use biological weapons. The argument is that biological weapons cannot be controlled, meaning that the weapon could harm the offensive forces. An agent like smallpox or other airborne viruses would almost certainly spread worldwide and ultimately infect the user's home country.

It has also been suggested that the development of BW agents requires a degree of sophisticated science and technology. However, this argument does not necessarily apply to bacteria. For example, an anthrax agent can easily be produced and controlled in a high school laboratory at a very small cost. Also, using standard microbiological methods, bacteria can be suitably modified to be effective in only a narrow environmental range, and be rendered antibiotic resistant.

A biological weapon may be further used to bog down an advancing army making them more vulnerable to counterattack by the defending force. Note that these concerns generally do not apply to biologically derived toxins, which while classified as biological weapons, the organism that produces them is not used on the battlefield, so they present concerns similar to chemical weapons.

History

As early as 400 BC, Scythian archers infected their arrows by dipping them in decomposing bodies or in blood mixed with manure. Greek, Persian and Roman authors from 300 BC quote examples of the use of animal bodies to contaminate wells and other sources of water.In the 12th century AD, during the Siege of Tortona, Barbarossa used the bodies of dead soldiers to poison wells. They also used primitive chemical warfare agents including sulfur dioxide. In the 14th century AD, during the Siege of Kaffa (1346), the attacking Tarter force hurled the bodies of plague victims into the city to attempt to inflict a plague epidemic upon the enemy.

During the French and Indian War (1754-1763) the British gave blankets from smallpox patients to the Native Americans to transmit the disease to the native tribes who would have had no immunological defence as the disease was unknown in North America.

During the American Civil War, a Confederate surgeon was arrested and charged with attempting to import yellow fever-infected clothes into the northern parts of the United States, again as a crude attempt at biological warfare. During World War I, the Germans developed anthrax, glanders, cholera, and the wheat fungus Claviceps spp. for use as biological weapons. They used Burkholderia mallei (the cause of glanders in horses) to infect horses being shipped from neutral countries to the UK and to France. They allegedly spread plague in St. Petersburg, Russia, Despite the fact that the Geneva Protocol of 1925 forbad the use of biological warfare agents the Germans, Japanese, UK, USSR and USA all experimented with a variety of germ warfare agents during WWII. Anthrax and botulinum toxin initially were investigated by the USA for use as weapons, and sufficient quantities of botulinum toxin and anthrax cattle cakes were stockpiled by June 1944 to allow limited retaliation if the Germans first used biological agents. The USSR developed Francisella tularensis as a weapon and used it in 1942 against German troops during the Battle for Stalingrad, there were over 100,000 victims, significantly extremely large numbers of Soviet troops were also infected. Unit 731 operated Japan's secret germ warfare program. Rumours of the unit's activities in northern China had been circulating in Russia and the West since the late 1930s, but the details finally emerged through captured documents and the testimony of Japanese prisoners of war, when the unit was captured by the Soviets in 1945. The unit, commanded by Lieutenant General Shiro Ishii, experimented with anthrax, dysentery, cholera, and plague on as many as 3,000 U.S., British, and Commonwealth POWs. The Japanese had used crude BW weapons against the Chinese when they invaded Manchuria, causing some 6,00 deaths. They also attempted to attack the US mainland using balloons carrying fleas infected Yersinia pestis. It was not until 1988 that the Japanese acknowledged what had happened.

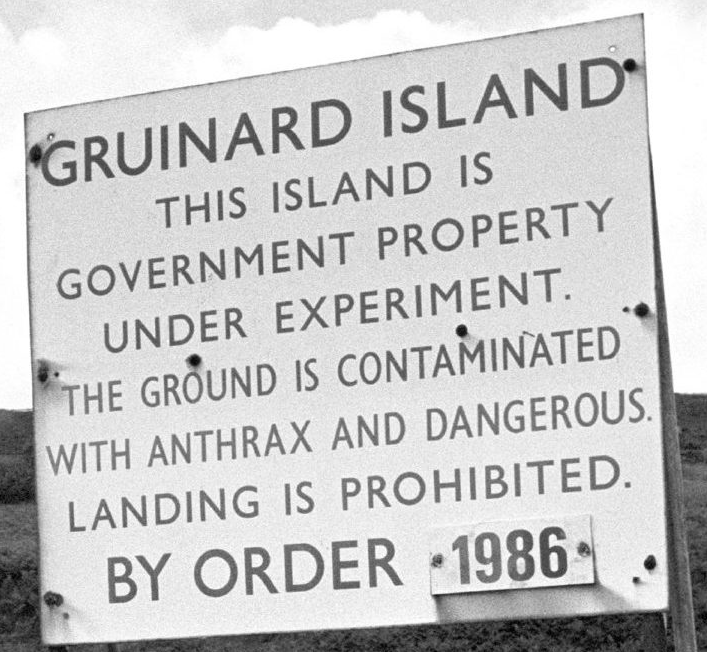

The British certainly experimented with Bacillus anthracis the cause of anthrax, most famously with anthrax spore bombs on Gruinard Island off the coast of Scotland in 1942. They exploded bombs containing B. anthracis on the island near restrained sheep, the sheep started to die after three days. This demonstrated the effectiveness of the weapon, unfortunately the island was then heavily contaminated with anthrax spores and couldn't be used for nearly 50 years, in fact it took several years to decontaminate the soil using formaldehyde (formalin diluted in seawater to give a 4% formaldehyde) solution. At the same time the Ministry of Agriculture were making large volumes of anthrax vaccine at the Central Veterinary Laboratory at Weybridge in Surrey (in C-Block, framed in red, this is a recent picture and most of the buildings shown did not exist at that time, the webmaster actually worked in this building in the late sixties, but on animal health issues, not BW.

The UK also experimented with several other agents during WWII, including glanders. The work on glanders had been ongoing since the 1st World War, and was primarily concerned with the development of diagnostic tests and vaccines, and was conducted mainly at the Central Veterinary Laboratory, under the leadership of Norman H. Hole, in the Pathology Department.

Gruinard Island Anthrax Experiment (1942)

Cold War

The

development of BW agents continued into the Cold War in the UK,

USSR, USA, and certainly other countries. The UK unilaterally

stopped biological weapon development in 1956, but continued work

of a defensive nature at the Microbiological

Research Establishment, Porton Down.

Operation Cauldron (1952)

Operation Cauldron was a series of

secret biological warfare trials undertaken by the British

government in 1952, in collaboration with the US. Scientists

from Porton Down and the Royal Navy were involved in releasing

biological agents, including pneumonic and bubonic plague,

brucellosis and tularaemia and testing the effects of the agents

on caged monkeys and guinea pigs. While

the tests were carried out by Britain, the tests were a joint

Anglo-US-Canadian operation, with a US Navy Lieutenant

Commander taking part. US documents showed that the

operation was not purely defensive, as later claimed; at a joint

1958 conference in Canada the US chemical corps minuted "it

was agreed ... studies should be continued on aerosols ... all

three countries should concentrate on the search for

incapacitating and new-type lethal agents". During the

trial a Fleetwood trawler, "Carella" ignored the exclusion order

and was contaminated with Yersinia pestis the cause of

plague.

Operation Harness was a

series of three-month secret biological warfare trials carried

out by the government of the United Kingdom in the Caribbean,

off The Bahamas, in December 1948 - February 1949, again in

collaboration with the US. Animals were exposed to Bacillus

anthracis, Francisella

tularensis, and Brucella

spp. bacteria on inflatable dinghies offshore but

the results were found meaningless. Bacillus

subtilis was used as a non hazardous tracer

organism.

The operation did not go well, for several reasons. The sea was

rougher than expected, making it impossible for the dinghies

with animal crates to be picked up by craft converted for the

operation. This meant the tests were carried out just off the

shore of an island, endangering inhabitants. Protective suits

were found to be so heavy that those using them had to undergo a

lengthy acclimatisation process to avoid heat exhaustion.

Sampling equipment was accidentally activated by local radio

signals and conditions at sea made it impossible to accurately

measure the amount of bacteria in the atmosphere.

500 of 600 sheep were found to be unsuitable and were shot.

Guinea pigs were found to be "disastrous". 234 rhesus macaques

had to be treated for pneumonia before being used.

The official report found that the techniques used were over

complicated, and said that it was "uncommonly lucky" that only

one of the staff was infected.

Operation Cauldron (1952)

The operation did not go well, for several reasons. The sea was rougher than expected, making it impossible for the dinghies with animal crates to be picked up by craft converted for the operation. This meant the tests were carried out just off the shore of an island, endangering inhabitants. Protective suits were found to be so heavy that those using them had to undergo a lengthy acclimatisation process to avoid heat exhaustion.

Sampling equipment was accidentally activated by local radio signals and conditions at sea made it impossible to accurately measure the amount of bacteria in the atmosphere.

500 of 600 sheep were found to be unsuitable and were shot. Guinea pigs were found to be "disastrous". 234 rhesus macaques had to be treated for pneumonia before being used.

The official report found that the techniques used were over complicated, and said that it was "uncommonly lucky" that only one of the staff was infected.

Operation Ozone (1954)

Dragonfly helicopter spraying BW simulant zinc cadmium sulphide on Lulworth Range August 1957

The Lyme Bay Trials

In 1969, the UK and the Warsaw

Pact, separately, introduced proposals to the UN to ban

biological weapons, and US President Richard Nixon terminated

production of biological weapons, allowing only scientific

research for defensive measures. The Biological

and Toxin Weapons Convention was signed

by the US, UK, USSR and other nations, as a ban on "development,

production and stockpiling of microbes or their poisonous

products except in amounts necessary for protective and

peaceful research" in 1972. Signatories to this agreement

are required to submit information annually to the United

Nations concerning facilities where biological defense research

is being conducted, scientific conferences that are held at

specified facilities, exchanges of scientists or information,

and disease outbreaks. The United States terminated its

offensive biological weapons program in 1969 for microorganisms

and in 1970 for toxins. American stockpiles of biological

weapons were destroyed completely by 1973. However, the Soviet

Union continued research and production of offensive biological

weapons in a program called Biopreparat,

despite having signed the convention. Currently some 165

countries have signed the treaty and none are proven, though ten

are still suspected, to possess offensive BW programs. The

Soviet Union continued to develop biological weapons from

1950-1980. In the 1970s, the USSR and its allies were suspected

of having used "yellow rain" (trichothecene

mycotoxins) during campaigns in Loas,

Cambodia, and Afghanistan. During

the Vietnam War, the Vietcong used punji

stakes dipped in faeces to increase

the morbidity from wounding by these stakes.

In 1985, Iraq began an offensive biological weapons program

producing anthrax,

botulinum toxin, and aflatoxin. During Operation Desert

Shield, the coalition of allied forces faced the threat of

chemical and biological agents. Following the Persian Gulf

War, Iraq disclosed that it had bombs, Scud missiles, 122-mm

rockets, and artillery shells armed with botulinum toxin,

anthrax, and aflatoxin. They also had spray tanks fitted to

aircraft that could distribute 2000 Litres over a target.

Currently some ten or so countries are suspected of having an

offensive biological warfare program.

Bio-terrorism

Since the 1980s a number of

terrorist organisations have used biological agents. The most

frequent bioterrorism episodes have involved contamination of

food and water. In September and October of 1984, 751 persons

were infected with Salmonella

typhimurium after an intentional

contamination of restaurant salad bars in Oregon by followers of

the Bhagwan

Shree Rajneesh.

In 1994, members the Japanese Aum

Shinrikyo cult attempted an aerosolized

release of anthrax from the tops of buildings in Tokyo. In 1995,

two members of a Minnesota

militia group were convicted of

possession of ricin, which they had produced themselves for use

in retaliation against local government officials. In 1996, an

Ohio man was able to obtain Yersinia

pestis, the cause of plague, cultures through the

mail.

During 1998 and 1999, multiple

hoaxes occurred in the USA, involving the threatened release of B.

anthracis. Nearly 6,000 persons across the United

States have been affected by these threats.

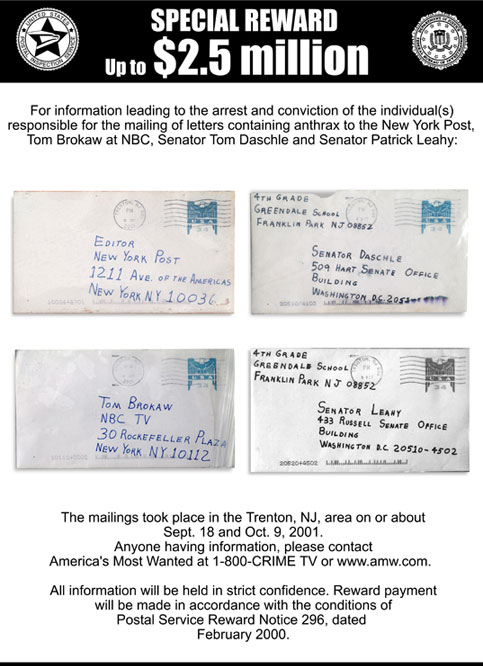

From

September to November 2001, a total of 23 confirmed or

suspected cases of bioterrorism-related anthrax (10

inhalation, 13 cutaneous) occurred in the United States. Most

cases involved postal workers in New Jersey and Washington DC,

and the rest occurred at media companies in New York and

Florida, where letters contaminated with anthrax were handled or

opened. As a result of these cases, approximately 32,000 persons

with potential exposures initiated antibiotic prophylaxis to

prevent anthrax infections.

According

to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC), an intentional release of anthrax by a bioterrorist in a

major US city would result in an economic impact of $477.8 million

to $26.2 billion per 100,000 persons exposed.

Categories of agents

The

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classify

biological agents based on the ease of transmission, severity of

morbidity, mortality, and likelihood of use, into 3 categories.

Category A includes the highest

priority agents that pose a risk to national security because of

the following features:

- They can be easily

disseminated or transmitted person-to-person causing secondary

and tertiary cases.

- They cause high mortality

with potential for major public health impact including the

impact on health care facilities.

- They may cause public

panic and social disruption.

- They require special

action for public health preparedness.

Category

B Agents contains the second highest

priority agents because they:

- They are moderately easy

to disseminate

- They cause moderate

morbidity and low mortality

- They require specific

enhancement of CDC's diagnostic capacity and enhanced disease

surveillance

Category

C Agents contains agents with the

third highest priority include emerging pathogens that could be

engineered for mass dissemination. The characteristics that render

them amenable to bioterrorism are:

- Availability

- Ease of production and

dissemination

- Potential for high

morbidity and mortality and major health impact.

Possible

BW Agents

N.B.

The classification and naming of organisms (taxonomy) changes over

time, perhaps more frequently in microbiology than many other

areas of the biological sciences. As an example the cause of glanders in

man and animals has been known as: Glanders

bacillus, Corynebacterium mallei, Mycobacterium

mallei, Bacillus mallei, Actinobacillus

mallei, Pfiefferella mallei, Malleomyces

mallei, Loefflerella mallei, Acinetobacter

mallei, Pseudomonas mallei and

is now known, at the time of writing, as Burkholderia

mallei.

The letters in (brackets) represent the NATO military codename(s).

The letters in [square brackets] represent the National

Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID)

classification of organisms., as described above. Several groups

of organisms could be used in biologic warfare:

Bacteria

Bacteria

(singular: bacterium) are microscopic, single-celled organisms

that thrive in diverse environments. Thay can live in soil, the

ocean, thermal springs and inside and on the human body.

Human relations with bacteria are complex. Sometimes

bacteria, are helpful such as by turning milk into yogurt or

cheese. In other cases, bacteria are destructive, causing diseases

like pneumonia and tuberculosis.

Bacteria are classified as prokaryotes, which are single-celled

organisms with a simple internal structure they lack a nucleus,

and contain DNA that either floats freely in a twisted,

thread-like mass called the nucleoid, or in separate, circular

pieces called plasmids. Ribosomes are spherical units in the

bacterial cell where proteins are assembled from individual amino

acids using the information encoded in ribosomal RNA.

Bacterial cells are generally surrounded by two protective

coverings: an outer cell wall and an inner cell membrane. Certain

bacteria, like the mycoplasmas, do not have a cell wall at all.

Some bacteria may even have a third, outermost protective layer

called the capsule. Whip-like extensions often cover the surfaces

of bacteria - long ones called flagella or short ones called pili

- that help bacteria to move around and attach to a host.

Protozoa

Protozoa

are eukaryotic unicellular organisms, which together with

single-cell algae and slime molds belong to the Protista kingdom.

The protozoans contain a membrane-surrounded nucleus and cellular

organs. Most protozoa have, at least in some stage of their life,

structures such as flagella or cilia that enable them to move and,

for some species, to obtain nutrients. Most protozoa are

microscopical. They live in moist conditions and only a few are

parasites. Protozoans usually multiply asexually by binary or

multiple fission. Some are capable of sexual reproduction.

Intestinal protozoans infect faeco-orally and cause

gastrointestinal signs to dogs. Some vector-borne protozoans may

cause generalized clinical signs that involve many

organs.Infections caused by protozoa can be spread through

ingestion of cysts (the dormant life stage), sexual transmission,

or through insect vectors.

Protozoa are broken down into different classes:

- Sporozoa (intracellular

parasites)

- Flagellates (with

tail-like structures that flap around to move them)

- Amoeba (which move using

temporary cell body projections called pseudopods)

- Ciliates (which move by

beating multiple hair-like structures called cilia)

- Many common -and not so

common - infections are caused by protozoa. Some of these

infections cause illness in millions of people each year;

other infections are rare and may be disappearing.

Viruses

Viruses

are infectious agents that can only replicate within a host

organism, in other words they are obligate parasites. They can

infect a variety of living organisms, including bacteria, plants,

and animals. They are extremely small, most being too small

to be seen under a light microscope, they have a very simple

structure. When a virus particle is independent from its host, it

consists of a viral genome, or genetic material, contained within

a protein shell called a capsid. In some viruses, the protein

shell is enclosed in a membrane called an envelope. Viral genomes

are very diverse, since they can be DNA or RNA, single or

double-stranded, linear or circular, and vary in length and in the

number of DNA or RNA molecules.

The viral replication process begins when a virus infects its host

by attaching to the host cell and penetrating the cell wall or

membrane. The virus's genome is is released from the protein

and injected into the host cell. Then the viral genome hijacks the

host cell's control mechanisms, forcing it to replicate the viral

genome and produce viral proteins to make new capsids. Next, the

viral particles are assembled into new viruses. The new viruses

burst out of the host cell during a process called lysis, which

kills the host cell. Some viruses take a portion of the host's

membrane during the lysis process to form an envelope around the

capsid.

Following viral replication, the new viruses may go on to infect

new hosts. Many viruses cause diseases in humans, such as

influenza, chicken pox, AIDS, the common cold, SARS, and rabies.

The primary way to prevent viral infections is vaccination, which

administers a vaccine made of inactive viral particles to an

unaffected individual, in order to increase the individual's

immunity to the disease.

Fungi

Fungi (singular fungus) are

eukaryotes and are an extremely diverse group including yeasts,

moulds and mushrooms. They, unlike most other organisms have

chitin in their cell walls. Fungi are heterotrophs, absorbing

their food by directly from their environment. Typically they

secrete digestive enzymes into their surroundings. They are

non-photosynthetic. Except for the flagellated spores of a few

species, fungi are non-motile. Fungi are separate from

structurally similar slime moulds. Most fungi are inconspicuous

due to their small size and their lifestyles, many only become

visible during the fruiting or reproductive phases. Fungi have

long been used as a food source - mushrooms - or in the making

of food and drink - as yeasts in the making of bread and

alcoholic beverages.

There are an estimated 2.2 million

species, most of which have yet to be studied.

Relatively few fungi are

pathogenic to man, although some produce mycotoxins which can

cause fatal consequences. Fungi do cause considerable

impact as agents of plant disease and spoilage of food products.

Toxins

Biological

toxins are poisonous by-products of microorganisms, plants, and

animals that produce adverse clinical effects in humans, animals,

or plants. A toxin has been defined as "a poisonous substance that

is a specific product of the metabolic activities of a living

organism and is usually very unstable, notably toxic when

introduced into the tissues, and typically capable of inducing

antibody formation" (Merriam-Webster Dictionary). Biological

toxins include metabolites of living organisms, degradation

products of dead organisms, and materials rendered toxic by the

metabolic activity of microorganisms. Some toxins can also be

produced by bacterial or fungal fermentation, the use of

recombinant DNA technology, or chemical synthesis of

low-molecular-weight toxins. Because they exert their adverse

health effects through intoxication, the toxic effect is analogous

to chemical poisoning rather than to a traditional biological

infection. Biological toxins are produced by certain bacteria,

fungi, protozoa, plants, reptiles, amphibians, fish, echinoderma

(spiny urchins and starfish), mollusks, and insects.

Biological weapons

Infectious agents or toxins are

not of themselves biological weapons, they have to be

weaponised. This means three things chiefly:

- they must be made

available in a form that may be stored, in the case of

spore forming organisms this is relatively easy. Freeze-drying

(lyophilisation) may well be an option using technology

commonly used in vaccine production.

- they must be capable of

being delivered to the target in such a way as to be

effective.

- a delivery system has to

be available, this could be simply an atomiser, or in the case

of dry spores it could be an explosive device as was used in

the UK's Gruinard Island experiments shown in the video above.

Probably the simplest delivery system used in recent years was

the post.

Biological warfare research sites:

United States

United States

- Fort

Detrick, Maryland (1943-69)

-

Horn Island Testing Station (1943-46)

-

Fort Terry (1952-69)

-

Granite Peak Installation (1943-45)

-

Vigo Ordnance Plant (1942-47)

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

USSR

USSR

- Biopreparat

- 18 labs and production centers (1973-91)

-

Stepnagorsk

Scientific and Technical Institute for Microbiology,

Stepnogorsk, northern Kazakhstan (1982-91)

-

Institute

of Ultra Pure Biochemical Preparations, Leningrad, a

weaponized plague center (1974-91)

-

Vector

State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology (VECTOR),

a weaponized smallpox center (1974-2020)

-

Institute

of Applied Biochemistry, Omutninsk (1988-1991)

-

Kirov

bioweapons production facility, Kirov, Kirov Oblast

-

Zagorsk smallpox production facility, Zagorsk

-

Berdsk

bioweapons production facility, Berdsk

-

Bioweapons

research facility, Obolensk

-

Sverdlovsk

bioweapons production facility

-

Vozrozhdeniya

Japan

Japan

- Unit 731 (1937-45)

-

Zhongma

Fortress (1930-37)

Iraq

Iraq

- Al

Hakum (1989-1991)

-

Al

Hazen Ibn Al Haitham Institute (1974-78)

-

Salman

Pak facility (1979-1985)

-

Ibn

Sina Centre

-

Al

Manal facility (1993-??)

-

Al

Taji (1978-87)

South Africa

South Africa

- Delta

G Scientific Company (1982-93)

-

Roodeplaat

Research Laboratories (1983-93)

Canada

Canada

- Grosse

Isle, Quebec (1939-45)

-

Experimental

Station Suffield, Suffield, Alberta (1950-68)

Cold War Trials

From

1950 until 1978 UK scientists, occasionally in collaboration with

the USA, conducted numerous trials in the UK, where biological

agent simulants were sprayed or otherwise disseminated over large

areas of the UK. Such simulants included fluorescent powder and

dead or living bacteria (Serratia

marcescens, Bacillus globigii (now

known as B.

subtilis ) and Escherichia

coli). Other experiments subjected animals to

infection with biological warfare agents. Similar tests were

conducted by the USSR using Serratia

marcescens and Bacillus

thuringensis, including tests on the Moscow Metro

with the latter organism.

In

1979, an accidental release of anthrax from a weapons facility

in Sverdlovsk, USSR, killed at least 66 people this was denied

until 1992.

Operation

Cauldron (1952)

Film

of a secret Biological Warfare Trial in 1952. The tests were

conducted jointly by the Microbiological Research Establishment

(Porton Down) and the Royal Navy near the Isle of Lewis in the

Outer Hebrides. Live bacteria of several species, including Yersinia

pestis (plague) were sprayed into the air exposing

guinea pigs and monkeys to infection. The reference to this

experiment on Wikipedia refers to an airport in Venezuala (Merida,

ICAO designator MRD) as a source of some material, this is due to

a confusion over the letters NRD, probably miss-heard MRD,

which actually refer to the Naval Replenishment Depot. The pontoon

was part of the "Mulberry" floating harbour scheme used in WWII. WARNING you may find some of this film

disturbing.

Operation Ozone 1954

This

is a follow-up film to "Operation Cauldron", which I advise

watching first.

The Lyme Bay Trials (1966)

Biological

Warfare trials undertaken by the UK Government in 1966. The

trials were performed by the Microbiological Research

Establishment, Porton Down. They involved spraying viable bacteria

into the air, and tracing their spread over Dorset and the

surrounding areas.

Civil Defence Corps

The

Civil Defence Corps continued BW protective training until 1968.

This was extremely basic, from memory one 1 hour

lecture/demonstration as the rapid identification of organisms, or

even the identification that an attack had taken place was not

possible at that time. They worked on the assumption that if there

had been an explosion of relatively low power, and no chemical

agent had been identified, that a BW attack had taken place. Of

course this ignores the fact that there are other methods of

disseminating BW agents, e.g. spraying, or polluting water

supplies. In any case the basic protection was the same, one wore

a respirator which protected against inhalation of agents, and

underwent the same decontamination procedures as for chemical

agents. If there was a high risk an NBC suit would have been worn.

In 1985, Iraq began an offensive biological weapons program producing anthrax, botulinum toxin, and aflatoxin. During Operation Desert Shield, the coalition of allied forces faced the threat of chemical and biological agents. Following the Persian Gulf War, Iraq disclosed that it had bombs, Scud missiles, 122-mm rockets, and artillery shells armed with botulinum toxin, anthrax, and aflatoxin. They also had spray tanks fitted to aircraft that could distribute 2000 Litres over a target.

Currently some ten or so countries are suspected of having an offensive biological warfare program.

United States

United States United Kingdom

United Kingdom USSR

USSR Japan

Japan Iraq

Iraq South Africa

South Africa Canada

CanadaOperation Ozone 1954

This is a follow-up film to "Operation Cauldron", which I advise watching first.