Civil Defence Corps

I was fortunate enough and am proud to have served in the Civil Defence Corps for the last four years of its existence. I was initially a member of the Headquarters section, Signal B sub-section, but transferred to the Ambulance and First Aid section. Although its primary role was seen as being in the event of nuclear war, it had also proven its worth in natural disasters and accidents, including the East Coast floods of 1953, several train crashes (Harrow & Wealdstone, Lewisham and Sutton Coldfield), and the Aberfan disaster. Since then, many people have questioned whether or not the volunteers would have responded in the event of war, remember 1,900,000 served and 6,200 members of the WWII Civil Defence Services, gave their lives. The Corps was formed in response to the 1948 Civil Defence Act, and the issuance of a Royal Warrant. The Act imposed on Local Authorities a number of functions under the Civil Defence (Public Protection) Regulations, 1949. Local Authorities became "Corps Authorities", they were required to form divisions of the Civil Defence Corps and to recruit, organise and train volunteers.

The functions of the Corps were:

- The collection of intelligence on the results of hostile attack

- Control and coordination of action as a result of the attack

- Rescue

- Protection against the effects of nuclear, biological or chemical attack

- Instruction and advice to the public

Despite an oft-repeated error, the

Civil Defence Corps had no connection with the Territorial Army,

they were a strictly civilian organisation, the Home Office being

the relevant Government department with overall control. We did,

however exercise together on occasion.

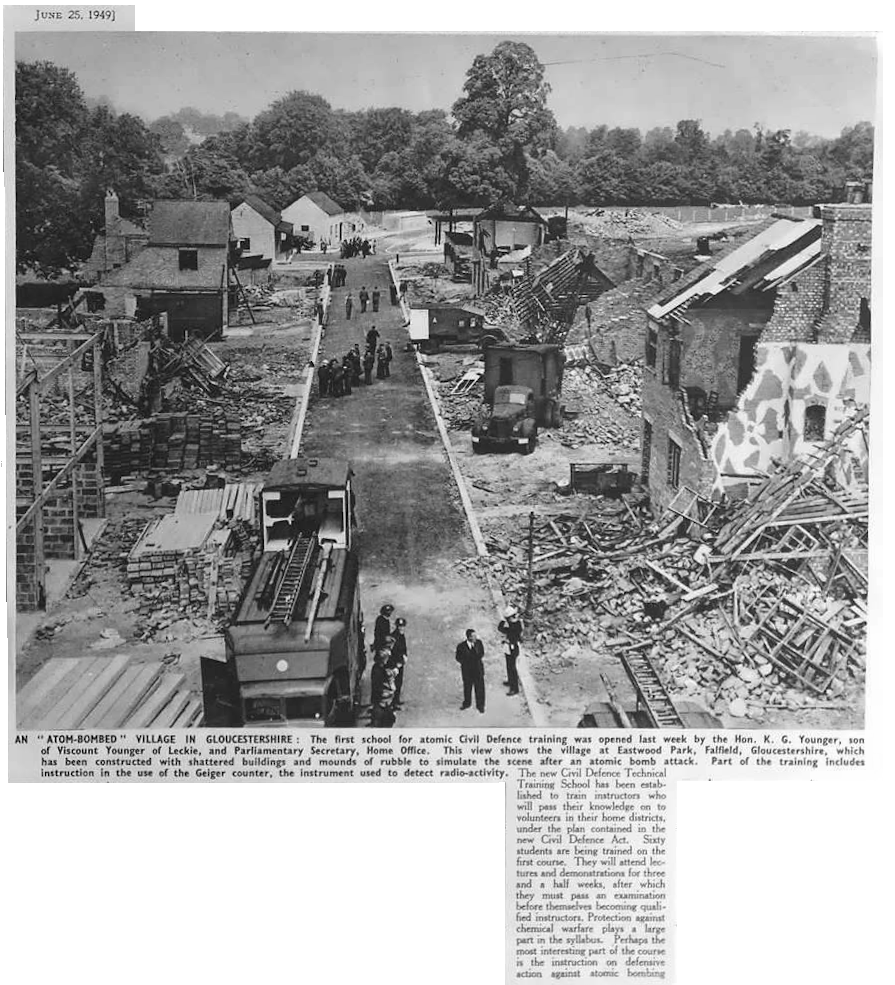

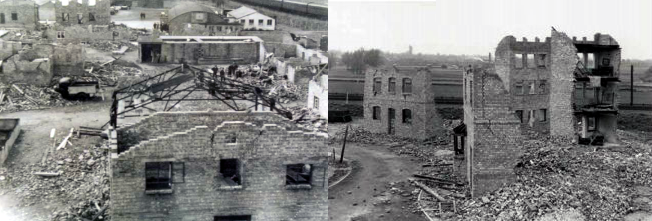

At the end of June 1950 the Corps in England and Wales had a strength of 31,000, many of whom had been in WWII Civil Defence. By the end of March, 1956 there were 330,000 members. Instructors and officers had been largely recruited from member of WWII Civil Defence or retired member of the armed forces. Training for officers and instructors had begun at the Home Office Civil Defence Technical Schools, one at Eastwood Park in Falfield, Gloucestershire, and the other at Easingwold, Yorkshire, in 1949. In 1950 a further school opened at Taymouth Castle in Scotland. The Home Office Staff College also opened at Sunningdale in 1950.

In the early days of the Corps training was based upon the experiences of 1939-45. It soon became apparent that this was not appropriate, and that the Corps would have been ill-equipped. In fact the Corps didn't receive RADIAC equipment for several years. In 1955 a whole new training scheme was introduced, with specific targets for volunteers.Despite a continuing recruitment programme, the Corps never achieved the hoped for strength, the maximum number of volunteers being 330,000 in 1956.

At the same time the role of Scientific Intelligence Officer was introduced, they were initially known as Technical Reconnaissance Officers. Their role was to advise controllers at all levels on technical matters relating to fallout, chemical weapons and the like.

Exercises formed a critical element of the training programme and were made as realistic as possible. Sections would undertake practical training exercises in addition to the larger scale exercises that were at Division or area level. A number of training sites were established, designed to resemble what might be found post attack.Training for the Corps was conducted during weekday evenings, comprising lectures, demonstrations, film shows and practical work. During the first session recruits were required to sign an Official Secrets Acts form. There were periodic tests, both practical and theoretical. Following initial training, common to all sections, and completion of the required tests, a uniform, lapel badge and ID card were issued. Initial training included basic first aid, Corps structure and organisation, Corps communications procedures, relationship of the Corps to other voluntary organisations, the police and military. Volunteers then went on to join sections where they received specialist training, also followed by tests.

Every few weeks there were longer one-day training sessions for sections, and once a year a large-scale exercise, involving a whole County at one of the Home Office Training Grounds. Additionally there were Divisional Exercises once a year, some of which were quite creative.

As an example of the latter, Excercise Thames involved evacuating over 1,000 people from the air raid shelters at the Vickers aircraft factory at Weybridge, to Walton on Thames using boats provided and crewed by local owners. Actually it was the same few hundred people evacuated and then returned by road several times. The exercise involved all sections. Casualties were rescued either from the cliff-tops of the car park at Vickers, or from the shelters. They were treated by members of the Ambulance and First Aid section. From there they were carried by ambulance to the top of one of the bridges over the River Wey, then walking casualties walked down to the boats, and others were lowered on stretchers. At the end of the river trip they were transferred to ambulances again and thence to the CDHQ, where members of the Welfare Section and the WVS fed them before they were sent around again. One incident in particular sticks in my mind, I was in the HQ Signal B sub-Section. By the time the Field cable party came to set up communications at the bridge, we had run out of field telephones, and we couldn't communicate between the top of the bridge and the boat embarcation point, we solved the problem by acquiring a garden hose together with two small funnels from a local hardware shop, and using them as a speaking tube.

The best way to describe the Civil Defence structure & organisation is to take that given in Handbook No 3, although there were minor variations over the years the basics remained the same, as examples in the early days there were a Pioneer section, and Rescue was divided into Light and Heavy Rescue.

ORGANISATION OF CIVIL DEFENCE CORPS

1. The Civil Defence Corps is a voluntary civilian organisation raised and trained by Corps Authorities which are, generally speaking, counties and county boroughs (in Scotland, counties and large burghs). Each Corps Authority raises a division of the Corps. The potential resources of manpower available to individual Corps Authorities for recruitment vary considerably. A division of the Civil Defence Corps is, therefore, not of fixed size. Local divisions of the Civil Defence Corps in England and Wales (except for London) are divided into the following sections:Headquarters, Warden, Rescue, Ambulance and First Aid, Welfare.

In London, the local divisions are organised by the City of London, and the Metropolitan Boroughs include Headquarters, Warden and Welfare Sections. The London County Council administers centrally the Rescue and Ambulance and First Aid Sections. The London County Council and the Metropolitan Boroughs share responsibility for the Welfare Section, the division of duties being on the broad basis of the peace-time functions of the respective authorities.

In Scotland, each local division is composed of four sections, namely:

Headquarters, Warden, Rescue and Welfare.

Organisation of Divisions.

1.2 In England and Wales, each local division of the Corps is composed of the five sections shown in succeeding paragraphs.

Headquarters Section. The Headquarters Section, which staffs control centres, is divided into three sub-sections:

(a) Intelligence and Operations Sub-Section - whose function is to analyse and record information and to prepare necessary instructions etc., at the controller's: direction.

(b) Signal Sub-Section - responsible for providing and maintaining communications (including wireless, field cable laying and despatch riders). (Later divided into Signal A - wireless & Signal B - field cable & despatch riders).

(c) Scientific and Reconnaissance Sub-Section - Whose primary task is to advise controllers about scientific and technical aspects of nuclear warfare (particularly as regards radioactive fall-out) and also on biological and chemical warfare as may be necessary. It is also responsible for the provision of staff for plotting and interpreting information about radioactive fall-out, and the provision of reconnaissance parties.

Warden Section. The wardens are the link between the civil defence services and the public to whom they will give leadership and guidance before, during and after attack. They are responsible for local reconnaissance and reporting, for the organisation of domestic 'self-help' parties and for the local control of life-saving civil defence services deployed within the warden post area. They have special responsibilities for measuring and reporting the degree of radioactivity of fall-out and for the control of the public. Rescue Section. This section is responsible for rescue work and first aid in connection with rescue operations, emergency work on demolition and debris clearance. Each party carries manpack equipment; heavier equipment is carried in a special vehicle.

Ambulance and First Aid Section. This section is built up on the normal peace-time ambulance service provided by county and county borough councils. The basic units of the section are the Ambulance Detachment and the First Aid Party and their duties are:

(a) Ambulance Detachment: the evacuation of casualties to Forward Medical Aid Units (see paragraph 1.7) and to hospitals.

(b) First Aid Party: to render first aid, to place seriously injured casualties on stretchers and to organize their removal to the ambulance loading points. In addition a certain number of ambulances will be retained for the work of the peace-time service.

Welfare Section. The Welfare Section will be concerned with the care of those rendered homeless as a result of war conditions or deprived of normal facilities for cooking, sanitation, etc. These duties will include work in connection with evacuation, rest centres for the homeless, billeting, emergency feeding, emergency sanitation, distribution of clothing, first aid, nursing the sick, information centres, etc.

In Scotland the functions of the Headquarters, Warden, Rescue and Welfare sections are similar to those in England and Wales. There is no separate ambulance and first aid section. The ambulance function is carried out by the Scottish Ambulance Service and the first aid function by the Warden Section. The latter has an element not found in England and Wales, namely, the casualty warden who is the specialist in first aid in the Section.

Pre-attack disposition of civil defence forces.

1.3 A proportion of the Section strengths (with the exception of the Warden and Welfare Sections) raised in Sub-regions and certain other densely populated districts will be stationed at operational bases for use in mobile columns after attack. The remaining strengths will comprise 'home cover' forces.

During the Cold War, Great Britain was divided into eleven Civil Defence regions each administered by a Regional Commissioner, ten of them in England, one each in Scotland and Northern Ireland. The commissioners were responsible for co-ordinating all local civil defence the Commissioners' role included the assumption of full state power after a nuclear attack. This required a large permanent staff from different government departments. In 1951 work commenced on the building thirteen war rooms in England, four of which were in Region 5 - London. The war rooms were designed to resist a near atomic explosion, and could operate for at least two weeks using a diesel generator to provide power, with an air conditioning plant room for filtered and cooled air. The rooms were rectangular with 4ft 10in thick reinforced concrete walls, and a 5ft thick roof with protected concrete vents at one end. Internally, the war rooms were similar to the wartime regional headquarters, but were on much a larger scale on two floors and included offices for different government departments, scientific advisers, the emergency services, a military liaison officer, canteen and welfare rooms, and dormitories and facilities for both male and female staff.

The Soviet detonation of their first hydrogen bomb, in 1953, caused a significant change in civil defence in the UK.Until that time most planning had been based on the notion of what was known as a nominal weapon of 20kT, similar to those used at Nagasaki and Hiroshima, or developments of them into the range of 100 kT or so. With yields in the megaton range, hydrogen bombs that could destroy great swathes of land and could affect wider areas for greater lengths of time, were potentially a completely different matter. In consequence, the post-explosion recovery period would be greater and each region would have to operate autonomously for longer, putting a great strain on the relatively small staff working in a war room. To provide for the greater manpower necessary to support the Commissioners, a system of Regional Seats of Government (RSG) was established starting in 1953, with the London war rooms abandoned altogether. The increase in staffing size (up to 400), resulted in new purpose-built war rooms being built adjoining the former war rooms at Cambridge and Nottingham, while other RSGs were established in abandoned RAF ROTOR bunkers, construction continued until 1963.

As soon as the RSGs come into service, it was realised that conditions after a nuclear strike might be even more fractured than first thought and a decision was taken to establish 25 Sub-Regional Headquarters (SRHQ), each accommodating a staff of up to 200 to assist during the recovery phase. By the end of the 1960s a number of SRHQs had been established in former army anti-aircraft operation room bunkers such as Frodsham (Cheshire). Others were constructed in purpose-built basements beneath new government buildings, as at the Civil Service Commission HQ, Basingstoke (Hampshire). The Home Office originally wanted 29 SRHQs, but financial restraints curtailed this and some were never built. This organisational structure was changed once again during the early 1980s, when England was divided into nine defence regions.

Council buildings constructed from the late 1930s often incorporate purpose-built civil defence headquarters, as in the case of Norwich where its CDHQ was beneath the City Hall, completed in 1938. During the Cold War, earlier headquarters were often re-used and modified to counter the effects of nuclear weapons. From the 1960s, as the armed forces abandoned bunkers these were often modified by local authorities, such as the former Anti-Aircraft Operations Room at Frodsham, Cheshire. Some local authorities also built new civil defence headquarters in the 1960s, including Walton and Weybridge UDC, who constructed a rather useless one in the semi-basement of the Town Hall. This was fully double-glazed, and kitted out when the Civil Defence Corps was disbanded in 1968. During the 1980s there was renewed interest in civil defence and a number of local authorities constructed purpose-built emergency centres.The Industrial Civil Defence Service (ICDS)

The ICDS was formed in 1951 when large companies were invited to form their own civil defence units. It had a similar organisation to the Civil Defence Corps, but was generally separate from it. The requirement was that a business employed two hundred or more people. These units were organised in a similar way to the Civil Defence Corps, with Headquarters, Warden, Rescue, First Aid and Fire Guard Sections. The Fire Guard Section manned fire points and smaller fire appliances, frequently based on Landrovers, there being no defined standard model. Each unit had its own control post, and groups of units could form a group control post. Group control posts and control posts in larger factories had the status of warden posts in their own right, whereas smaller units answered to their local Civil Defence Corps warden post. Companies that took part in the scheme included regions of British Railways, British Leyland, Norvic and Colmans. All of these organisations were largely manned by volunteers.

By 1956 there were over 200,000 volunteers in the ICDS, and over 50% of industries were involved. British Railways had a dedicated coach which traveled the network, for training purposes. The NCB (National Coal Board) had 20,000 volunteers, in addition to their regular mines rescue teams. The largest ICDS group was at the D. Napier and Sons aero engine factory at Acton, with 250 volunteers, they also had the country's first female rescue team.

Mobile Columns

Mobile columns were to be formed from the Welfare, First Aid & Ambulance, and Rescue sections. Each was to be headed up by an officer (Column Leader) with an assistant officer (Deputy Column Leader).

1967 Review and Disbandment

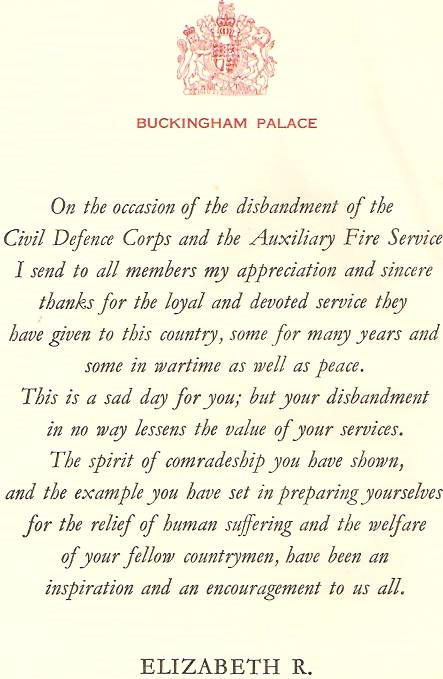

In 1967 an extensive review of Home Defence and Civil Defence planning, resulted in a considerable re-organisation and changes to minimum training requirements. Twice in that year (June and November) Lord Stonham, the Labour Minister of State for Civil Defence at the Home Office spoke of the essential nature of the Corps and the role of volunteers. Its came as a surprise, then, when Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced in the following January that the Corps, the ICDS and the Auxiliary Fire Service were to be disbanded at the end of March.The National Hospital Service Reserve was disbanded just over a year later.Upon disbandment each of the 75,000 member of the Corps received a copy of the letter shown, members were allowed to keep their uniforms! Equipment either went into storage or was issued to local Emergency Planning departments. Some was sold off almost immediately. Many RADIAC instruments and radios, appeared in electronics surplus shops in Lisle Street, Soho and similar premises throughout the UK. Most vehicles appeared on the surplus market within just a few years.

As far as the general public were concerned very little was done about civil defence until the 1980s, when Protect and Survive was produced, but even then it was not generally made public. At various times, generally in the wake of major accidents or natural disasters, there have been calls to reform the Corps. Government answers to such calls have always said that it would be prohibitively expensive.

The Civil Defence Long Service Medal

The Civil Defence Medal was instituted by HM Queen Ellizabeth II in March 1961 and awarded for 15 years continuous service in the Civil Defence Corps (CD), the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS), the National Hospital Service Reserve (NHSR) and the United Kingdom Warning and Monitoring Organisation. Qualification was extended in 1963 to Civil Defence personnel in Gibraltar, Hong Kong and Malta. On the UK mainland, only members of the United Kingdom Warning and Monitoring Organisation continued to qualify after the 1968 disbandment, until it too was disbanded in 1992 (the Warning and Monitoring Organisation on the Channel Islands of Jersey continued until 2007). The medal was awarded in Hong Kong until the territory was transferred to China in 1997. Prior service in the equivalent services of WWII counted when calculating total service. The medal is still awarded to members of the Isle Of Man Civil Defence Corps.

Today

The Civil Defence Corps still exists in the Isle of Man. The IOM Civil Defence Corps provides initial support for a variety of events. This may include re-homing individuals, families or communities as necessary, assisting with weather incidents or as part of the inland hill search and rescue team. It is involved in all kinds of emergencies, including mountain rescue, floods.