Chemical Warfare

Strictly speaking, a chemical weapon

relies on the physiological effects of a chemical, so agents used to

produce smoke or flame, as herbicides, or for riot control, are not

considered to be chemical weapons. Although certain chemical weapons

can be used to kill large numbers of people, as weapons of mass

destruction, other weapons are designed to injure or terrorise

people. In addition to having potentially horrific effects, chemical

weapons are of great concern because they are cheaper and easier to

manufacture and deliver than nuclear or biological weapons. Although

there are many thousands of chemical compounds that could

theoretically be used as chemical warfare agents, the actual number

that have been weaponised is relatively small, perhaps a few tens in

number.

The means available to adversaries for delivery of chemical weapons

range from specially designed, sophisticated weapon systems developed

by nations to relatively inefficient improvised devices employed by

terrorists and other disaffected individuals and groups. Any nation

with the political will and a minimal industrial capability could

produce chemical agents suitable for use in warfare. Efficient

weaponisation of these agents, however, does require design and

production skills usually found in countries that possess a munitions

development and production infrastructure or access to such skills

from cooperative sources. On the other hand, almost any nation or

group could fabricate crude agent dispersal devices. While such

methods may result in a small number of affected persons, the

psychological affect could be extremely significant.

Chemical agents have effects that can be immediate or delayed, can be

persistent or non-persistent, and can have significant physiological

effects. While relatively large quantities of an agent are required to

ensure an area remains contaminated over time, small-scale selective

use that exploits surprise can cause significant disruption and may

have lethal effects.

A

chemical weapon relies on the physiological effects of a chemical, so

agents used to produce smoke or flame, as herbicides, or for riot

control, are not considered to be chemical weapons. Although certain

chemical weapons can be used to kill large numbers of people, as

weapons of mass destruction, other weapons are designed to injure or

terrorise people. In addition to having potentially horrific effects,

chemical weapons are of great concern because they are cheaper and

easier to manufacture and deliver than nuclear or biological weapons.

Although there are many thousands of chemical compounds that could

theoretically be used as chemical warfare agents, the actual number

that have been weaponised is relatively small, perhaps a few tens in

number.

The means available to adversaries for delivery of chemical weapons

range from specially designed, sophisticated weapon systems developed

by nations to relatively inefficient improvised devices employed by

terrorists and other disaffected individuals and groups. Any nation

with the political will and a minimal industrial capability could

produce chemical agents suitable for use in warfare. Efficient

weaponisation of these agents, however, does require design and

production skills usually found in countries that possess a munitions

development and production infrastructure or access to such skills

from cooperative sources. On the other hand, almost any nation or

group could fabricate crude agent dispersal devices. While such

methods may result in a small number of affected persons, the

psychological affect could be extremely significant.

History

There is a considerable amount of evidence that chemical weapons usage goes back well into antiquity. Menes, the first pharaoh, certainly had a serious interest in toxicology in about 3,000 BCE. The Egyptians used hydrocyanic acid (hydrogen cyanide) [HCN]. Sulfur dioxide [SO2), from burning sulfur was used by the Greeks. Later both sulfur dioxide and arsenic [As] were proposed as weapons by Leonardo da Vinci.The use of poisons fell out of favor in the 18th and 19th century. In 1862, New York schoolteacher John W. Doughty wrote to the US Secretary of War suggesting methods of poison gas. This was dismissed and subsequently followed by a War Department General Order signed by President Abraham Lincoln stating that the use of poison should be "wholly excluded from modern warfare".

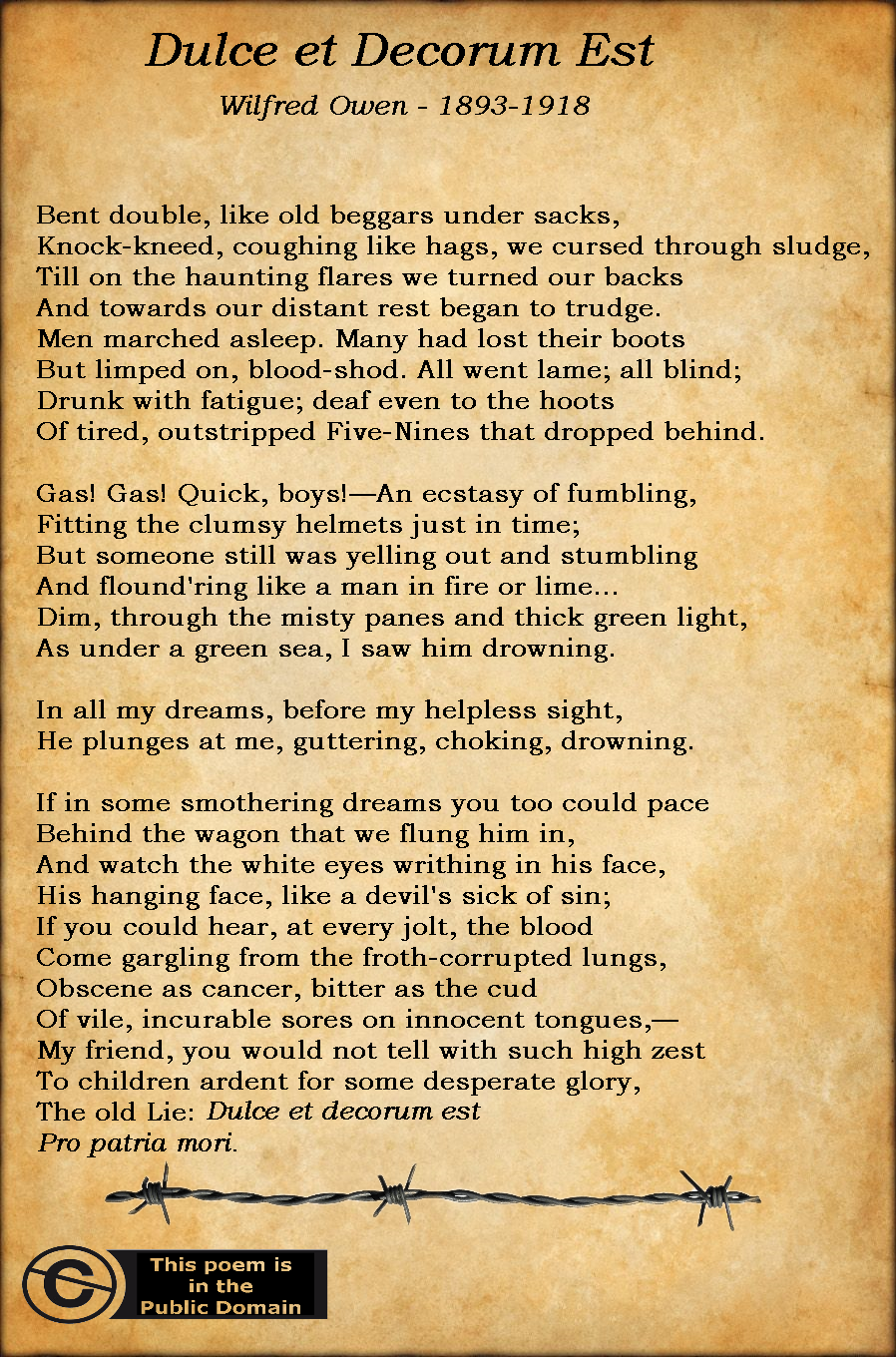

Chemical Weapons in World War I

At the beginning of World War I, the use of chemical weapons was still very much taboo. Not only did mankind have a universal aversion to the use of poison but there was also the 1899 Hague Convention. The modern use of chemical weapons began when both sides to the conflict used poison gas to inflict agonising suffering and to cause significant battlefield casualties. The first agent was ethyl bromoacetate [C4H7BrO2], a lachrymatory non-lethal agent. Such weapons basically consisted of well known commercial chemicals put into standard munitions such as grenades and artillery shells, or gases released from cylinders. Chlorine [Cl2], phosgene [COCl2] (a choking agent) and mustard gas (Bis(2-chloroethyl)sulfide) (ClCH2CH2)2S which inflicts painful burns on the skin and causes significant damage to the respiratory system) were among the first chemicals used. Chlorine was the first lethal chemical used, at the 2nd Battle of Ypres. The results were indiscriminate and often devastating. Nearly 100,000 immediate deaths resulted and many more suffered long-term damage leading to death from conditions such as emphysema, some casualties survived for many years but suffered continuous respiratory ill health. Since World War I, chemical weapons have caused more than one million casualties globally.

Inter-war years

As a result of public outrage, the Geneva Protocol, which prohibited the use of chemical weapons in warfare, was signed in 1925. While a welcome step, the Protocol had a number of significant shortcomings, including the fact that it did not prohibit the development, production or stockpiling of chemical weapons. Also problematic was the fact that many states that ratified the Protocol reserved the right to use prohibited weapons against states that were not party to the Protocol or as retaliation in kind if chemical weapons were used against them.

The chemicals employed before World War II can be styled as the "classic" chemical weapons. They are relatively simple substances, most of which were either common industrial chemicals or their derivatives. The classic chemical agents would be only marginally useful in modern warfare and generally only against an unsophisticated opponent, although they could be used in terrorist attacks, and have been used in Syria in modern times. Large quantities would be required to produce militarily significant effects, thus complicating logistics. In the case of terrorist attacks, relatively small amounts of an agent could cause significant casualties and disruption if used in some situations, for example in enclosed spaces such as shopping centres, concert halls or underground railway systems.

World War II

Chemical weapons were not used during WWII. Some claim of the use of Zyklon B, a commercial pesticide that released hydrogen cyanide gas, in the Nazi extermination camps was an example of chemical warfare. Zyklon B had been developed and produced by chemists Walter Heerdt, Bruno Tesch, and Gerhard Peters at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Dahlem. Zyklon B gas was not a chemical weapon; it is not, and has never been, subject to any international disarmament bans. After World War I and during World War II, it was the most commonly used pesticide in the world. It was first used on September 3, 1941 in the Auschwitz-Birkenau, by the initiative of the camp's first deputy commandant Karl Fritzsch. The first victims were Soviet prisoners of war who had been taken to Auschwitz, and 250 sick Poles.

Although both the axis and allied powers experimented with CW agents during WWII, they were not used, the reasons may be that they were following the proscription on their use under the Geneva Protocol, or that all civilians and troops were equipped with respirators and other protective measures.

Gerhard Schrader, a 33-year-old German chemist at the IG Farben chemical company, created what he called Preparation 9/91 (ethyl dimethylphosphoramidocyanidate, [C5H11N2O2P]), in 1936. Its intended use was as a pesticide, but it proved too effective and killed a wide range of organisms, including man. It was handed over to the military scientists of the Third Reich at Spandau Citadel, they were so impressed with its toxicity that they renamed the compound Tabun, the first nerve agent. He was paid 50,000 Marks (about US$20,000 or US$463,000 in 2025). Only two years later he developed another agent, Sarin. A third agent, Soman, was developed during the war. By the end of the war in excess of 50,000 tons of nerve agents had been produced, and many thousands of shells had been filled.

Cold War

During the Cold War, many nations researched chemical agents, possibly as many as twenty-five in all. Major research was certainly carried out in the USA, USSR and the UK, and chemical agents were weaponised and stockpiled by them.

United Kingdom

Work in the UK was centred on the Chemical Defence Experimental Establishment (CDEE), Porton. Ranajit Ghosh, a chemist at ICI, was investigating a class of organophosphate compounds for use as a pesticide. In 1954, ICI put one of them on the market under the trade name Amiton. It was subsequently withdrawn, as it was too toxic for safe use. The toxicity did not go unnoticed, and samples of it were sent to Porton Down for evaluation. After the evaluation was complete, several members of this class of compounds were developed into a new group of much more lethal nerve agents, the V agents. The best-known of these is probably VX, assigned the UK Rainbow Code Purple Possum, with the Russian V-Agent coming a close second (Amiton is largely forgotten as VG). Other members of the V series are VE, VG, VM and VR.

Gloster Meteor spraying Chemical Warfare simulant on the Porton Down Range (no audio)

On the defensive side, there were

years of work to develop the means of prophylaxis, therapy, rapid

detection and identification, decontamination and more effective

protection of the body against nerve agents, capable of exerting

effects through the skin, the eyes and respiratory tract.

Tests were carried out on servicemen to determine the effects of

nerve and other agents on human subjects, with one recorded death

due to a nerve gas experiment, that of 20 year old RAF airman Ronald

Maddison. It was 51 years before an inquest found

that he had died from sarin poisoning.

Operation Moneybags

In the 1950s the Chemical Defence

Experimental Establishment became involved with the development of CS,

a riot control agent, and took an increasing role in trauma and

wound ballistics work. Both these facets of Porton Down's work had

become more important because of the situation in Northern Ireland.

In the early 1950s, nerve agents such as sarin were produced, about

20 tons were made from 1954 until 1956 at CDE Nancekuke, in

Cornwall. Nancekuke was an important factory for producing and

stockpiling chemical weapons. Small amounts of VX were produced

there, mainly for laboratory test purposes, but also to validate

plant designs and optimise chemical processes for potential mass

production. In the late 1950s, the chemical weapons production

plant at Nancekuke was mothballed, but was maintained through the

1960s and 1970s in a state whereby production of chemical weapons

could easily re-commence if required. The site closed in 1978, and

reverted to being RAF Portreath, a radar station. It is now Remote

Radar Head Portreath or RRH Portreath an air defence radar station

operated by the Royal Air Force, as part of Programme

HYDRA.

United States

In 1958 the British government traded

their VX technology

with the United States in exchange for information on thermonuclear

weapons and by 1961 the U.S. was producing large amounts of VX and performing its own

nerve agent research. This research produced at least three more

agents; the four agents (VE, VG, VM, VX)

are collectively known as the "V-Series" class of nerve agents.

Between 1951 and 1969, Dugway

Proving Ground was the site of testing for

various chemical and biological agents, including an open-air

aerodynamic dissemination test in 1968 that accidentally killed, on

neighboring farms, approximately 6,400 sheep by an unspecified nerve

agent.

Project 112

From 1962 to 1973, the Department of

Defense planned 134 tests that was described as a chemical and

biological weapons "vulnerability-testing program", it was claimed

at the time that harmless simulants were used, but in 2002,

the Pentagon admitted that some of tests used real chemical and

biological weapons.

In October 2002, the Senate Armed Forces Subcommittee on Personnel

held hearings as the controversial news broke that chemical agents

had been tested on thousands of American military personnel. The

hearings were chaired by Senator Max Cleland, former VA

administrator and Vietnam War veteran.

Soviet Union

Due to the secrecy of the Soviet

Union's government, very little information was available about the

direction and progress of the Soviet chemical weapons until

relatively recently. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Russian

chemist Vil

Mirzayanov published articles revealing

illegal chemical weapons experimentation in Russia.

In 1993, Mirzayanov was imprisoned and fired from his job at the State

Research Institute of Organic Chemistry and Technology, where

he had worked for 26 years. In March 1994, after a major campaign by

U.S. scientists on his behalf, Mirzayanov was released. Among the

information related by Vil Mirzayanov was the direction of Soviet

research into the development of even more toxic nerve agents, which

saw most of its success during the mid-1980s. Several highly toxic

agents were developed during this period; the only unclassified

information regarding these agents is that they are known in the

open literature only as "Foliant" agents

(named after the program under which they were developed) and by

various code designations, such as A-230 and A-232.

According to Mirzayanov, the Soviets also developed binary weapons,

in which precursors for the nerve agents are mixed in a munition to

produce the agent just prior to its use. Because the precursors are

generally significantly less hazardous than the agents themselves,

this technique makes handling and transporting the munitions a great

deal simpler.

Additionally, precursors to the agents are usually much easier to

stabilize than the agents themselves, so this technique also made it

possible to increase the shelf life of the agents a great deal.

During the 1980s and 1990s, binary versions of several Soviet agents

were developed and designated "Novichok"

agents (after the Russian word for "newcomer").

Types of Agents

Chemical warfare agents can be classified in a variety of ways, based upon their properties, none of the schemes is totally satisfactory as some agents have effects which which fall into more than one group. The following is based upon the most generally held view.Choking agents (aka Pulmonary agents as they irritate the lungs)

Choking agents are delivered as gas clouds to the target area, where individuals become casualties through inhalation of the vapour. The toxic agent causes inflammation of the lungs and this causes fluids to build up in the lungs, which can cause death through asphyxiation. The effects may take up to three hours to be apparent. The long-term effects may last for many years.

Choking agents are not generally likely to be used in conventional warfare, but due to their ease of manufacture some have been used in recent years by countries that are not regarded as technologically advanced, and could also be used by terrorists.

Sternutators

Sternutators cause vomiting, respiratory irritation and sneezing, their purpose is to incapacitate rather than to kill the enemy.Lachrymators

Lachrymators cause irritation to the eyes, and hence tears. They are commonly called tear gas. Lachrymators are regarded now as riot control agents. Generally they cease to have any effect shortly after exposure ceases, although very high levels of exposure to some of the agents may cause long-term effects. The use of riot control agents as a method of warfare is prohibited by the CWC.Vesicants

Blister agents or vesicants are an exception to the limited utility of classic agents. Although these materials have a relatively low lethality, they are effective casualty agents that inflict painful burns and blisters requiring medical attention even at low doses.Blood agents

Blood agents, such as hydrogen cyanide [HCN]or cyanogen chloride [ClCN], are designed to be delivered in the form of a vapour or as a gas. When inhaled, these agents prevent the transfer of oxygen to the cells, causing the body to asphyxiate. Such chemicals block the enzyme that is necessary for aerobic metabolism, thereby denying oxygen to the red blood cells, which has an immediate effect similar to that of carbon monoxide. Cyanogen chloride inhibits the proper utilisation of oxygen within the blood cells.Nerve agents

Nerve agents interfere with nerve impulse transmission. They are a class of phosphorus containing organic chemicals (organophosphates) that disrupt the mechanism by which nerves transfer messages to organs. The disruption is caused by blocking acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme that normally destroys acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. They are related to DDT. They are the most toxic of CW agents.Nerve agents are now divided into three series:

- The G-series

- The V-series

- Novichoks

Psychotomimetic Agents

Psychotomimetic Agents are generally now not considered to be likely chemical warfare agents. They were experimented with in the 1950s-70s, but tend to be unstable and are difficult to deliver in sufficient concentration to be effective, as well as being very unpredictable in their effects.Toxins

As toxins are produced by living organisms they are chiefly considered on this site on the biological weapons page.Binary Agents

Binary weapons are defined as chemical warfare agents where the toxic agent is produced during the flight time of the ammunition (rocket, shell or grenade) on its way to the target.Civil Defence Corps

The Civil Defence Corps were trained in protection from chemical agents, and all of its personnel were specifically trained in the fitting of civilian respirators. The idea being that in the days leading up to the outbreak of hostilities all of the Corps would be expected to set up respirator fitting stations and to fit and supply everyone with a respirator, enough of which had been stockpiled to supply the whole country. Special respirators were available for the very young and the infirm, however these were just the WWII equivalents fitted with new filters. In fact, until about 1960 civilian respirators were all similar to the WWII versions, the only difference being the type of filter fitted.The Corps were supplied with the S6 respirator from the mid 1960s, which had a serious disadvantage, they could not be used with a radio operator's microphone, or a telephone. Initially personnel requiring this facility were supplied with a WWII Civilian Duty Respirator with an updated filter canister.

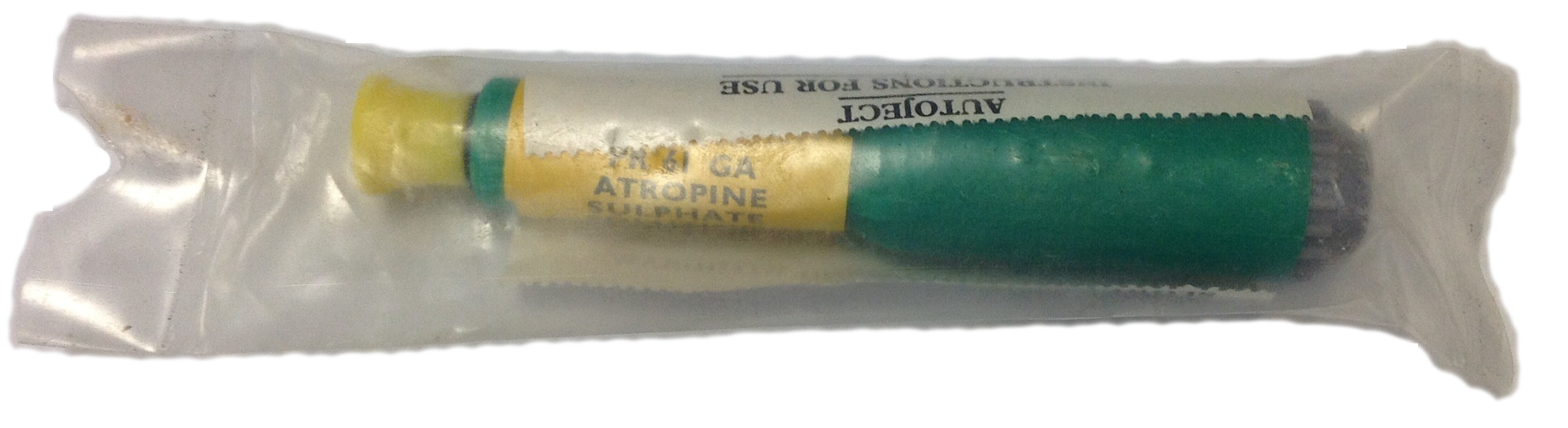

For the detection of chemical agents, three methods were available, the Paper Detector, of which there were several versions for liquid gas, detector paint which could be coated onto any suitable surface and the Kit Vapour Detector. During training we sniffed chemicals which were meant to smell like some of the chemical agents.The Civil Defence Corps were also supplied with respirator decontamination kits and anti-dimming kits. In wartime, personnel who were required to work outside would be supplied with NBC suits, which were initially heavy and cumbersome. During NBC training I wore the earlier lightweight suit for an hour doing moderate physical work (cable laying), and to be honest it was long enough. Just before the Corps was disbanded the suit NBC No 1 was issued, it was much improved being lighter and more flexible. The final item of kit was three rapid injection (Autoject) pens containing 1mg of atropine sulphate, to be used in the event of exposure to nerve agents. The instructions for using these was pretty basic, and amounted to "If you are in any doubt, then jab." To use this device, one simply removed it from the packaging, took off the cap, and with a swift movement jabbed it into the front of the thigh, right through any clothing. The other civil defence services were also supplied with the same types of equipment.